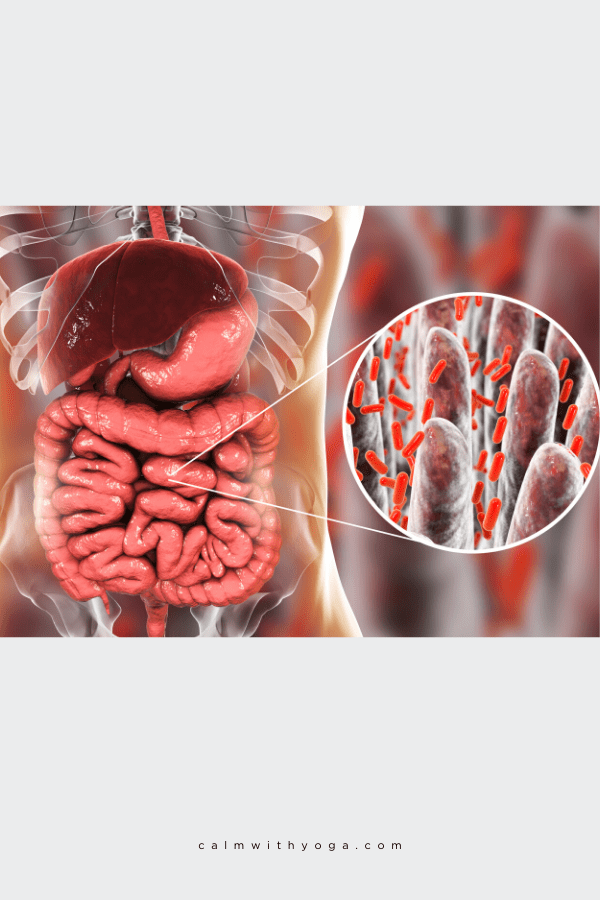

The human gut is like a universe, but instead of hosting trillions of stars and planets it hosts over 100 trillion bacteria that create what’s called the gut microbiome.

Your gastrointestinal tract has ten times more gut microbiota (gut flora) than human cells. (1)

There are 100,000 times more microbes in your gut alone as there are people on earth. (2)

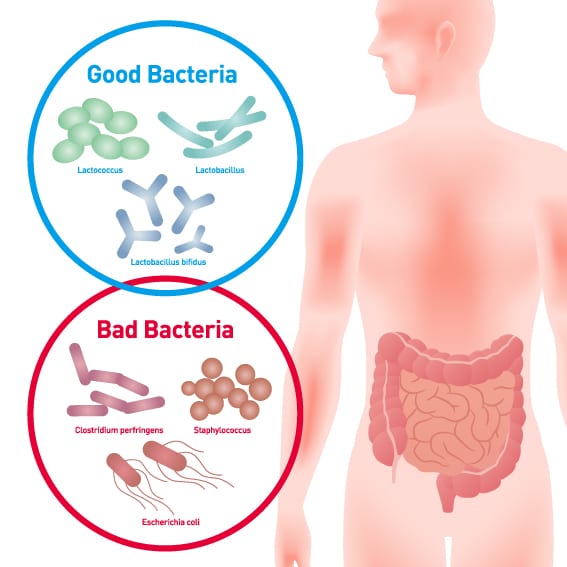

These microbes are either good bacteria (beneficial bacteria) or bad bacteria (harmful bacteria).

In order to maintain a healthy gut, you need more of the types of bacteria that are beneficial to your health.

These microbes play an essential role in your physical, emotional, and mental health and well-being.

Your quality of life is dependant on the state of your microbiome universe.

Gut health is very closely tied to mood and mind so when an imbalance in the gut occurs (dysbiosis) mood disorders can also arise.

This is because your gut microbes have an intimate relationship with the brain in your gut.

Yes, you have a brain in your gut. (Actually, the human body had three brains.)

The gut-brain is also known as the second brain or the enteric nervous system.

Your gut-brain is comprised of about 100 million nerve cells (neurons). (3)

Head brain cells, gut-brain cells, and gut bugs are all in constant communication sending and receiving information and impacting brain function.

This interplay is referred to as the Microbiota-Gut-Brain axis.

Imbalances in this interplay can lead to a dysregulated stress response and an overactive production of stress hormones.

Microbiome imbalances have been linked to chronic inflammation and health conditions such as leaky gut, irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease and have even been witnessed in clinically depressed patients.

10 Ways In Which The Bugs In Your Gut Impact Physical & Mental Health:

1. We have 360 times more bacterial genes than human genes in our bodies.

In this sense, we’re more bacteria than human. Microbiologists also reported that these microbes contribute more genes responsible for human survival than humans contribute. (4)

2. They help us digest and absorb nutrients from the food we eat.

According to Dr. Lita Proctor, program manager for the Human Microbiome Project: “Humans don’t have all the enzymes we need to digest our own diet. Microbes in the gut break down many of the proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates in our diet into nutrients that we can then absorb.” (4)

3. They influence the body’s immune response.

Approximately 80% of our immunity is located in the folds of your gut and these little bugs produce beneficial compounds that our bodies cannot produce on their own, compounds like vitamins and anti-inflammatories that regulate immune system activity. Bugs also support your immune system by preventing auto-immunity (when your body attacks its own tissues), and by communicating with and directing certain immune cells. (4)

4. They protect and shield us from harmful intruders like viruses, bad bacteria, and parasites.

Some bacteria have whip-like structures called ‘flagella’ that allow them to move or “swim,” and it’s been shown that they can protect against the nasty potentially lethal stomach rotavirus. (5)

5. A diversified microbiome can help keep us thin and healthy.

A study on obese and non-obese participants showed that individuals with low gut microbiota diversity are more often affected by obesity and low-grade inflammation than those whose microbiome was more diverse. (6)

6. Gut bugs help us detox.

They can help prevent infections and defend us from toxins.

One recent study titled: The Gut Microbiota: a Major Player in the Toxicity of Environmental Pollutants? concluded that:

“There is a body of evidence suggesting that gut microbiota are a major, yet underestimated element that must be considered to fully evaluate the toxicity of environmental contaminants.” (7)

7. They regulate our sleep-wake cycle, circadian rhythms, sleep hormones, and jet lag.

“Chronic jet lag is associated with loss of microbiota rhythms… The jet lag associated dysbiosis in mice and humans promotes metabolic imbalances.” (8)

New science confirms that our brains, guts, and gut microbes talk to each other in a shared biological language.

– Emeran Mayer, MD, author of: ‘The Mind-Gut Connection’

8. They help us manage stress, anxiety, and overwhelm by working alongside our hormonal system, aka: the endocrine system. (9)

9. Microbiome problems = feeling more pain.

An imbalance of “good” and “bad” gut bugs can change how we perceive pain, making us extra sensitive to it.

Various factors like mental/emotional stressors and infections can disrupt the harmony in your relationship with your gut bugs thereby also altering your pain response. (10)

10. Gut bugs are directly related to our anxiousness.

They produce and release molecules like enzymes and metabolites that interact with our biochemistry, including the very neurotransmitters responsible for how we feel and think – for example, serotonin and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid). (11)

A lot of progress has been made in understanding the link between our gut bugs and our prevalent anxiety and depression epidemic.

Most of the research and testing has been conducted on germ-free mice and other animal subjects, so it still remains to be seen how exactly this will all apply to humans.

So far, though, things are looking interesting.

A cover story by Dr. Siri Carpenter titled “That Gut Feeling” published by the American Psychological Association summarizes it well:

“Research has found, for example, that tweaking the balance between beneficial and disease-causing bacteria in an animal’s gut can alter its brain chemistry and lead it to become either more bold or more anxious.

The brain can also exert a powerful influence on gut bacteria; as many studies have shown, even mild stress can tip the microbial balance in the gut, making the host more vulnerable to infectious disease and triggering a cascade of molecular reactions that feed back to the central nervous system…

The new research also hints at new ways of managing chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders that are commonly accompanied by anxiety and depression, and that also appear to involve abnormal gut microbiota.” (12)

How To Keep Your Gut Bugs Happy With Psychobiotics:

We defined a psychobiotic as a live organism that, when ingested in adequate amounts, produces a health benefit in patients suffering from psychiatric illness.

As a class of probiotic, these bacteria are capable of producing and delivering neuroactive substances such as GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) and serotonin, which act on the brain-gut axis.

Preclinical evaluation in rodents suggests that certain psychobiotics possess antidepressant or anxiety-reducing activity.

Effects may be mediated via the vagus nerve, spinal cord, and neuroendocrine systems.

Recently we have suggested broadening the psychobiotic concept to include prebiotics – the fiber that acts as food for the psychobiotics.

– The Psychobiotic Revolution, by John Cryan & Ted Dinan

Probiotics:

Probiotics are live bacteria cultures. (Essentially, gut bugs.)

Common “good” gut bugs like lactobacillus and bifidobacterium are found in common probiotic supplements.

When we ingest these little guys a good amount of them reach the intestine in an active state and promote multiple beneficial health benefits, like helping keep your microbiome balanced so that there is no overgrowth of detrimental bacteria that can lead to infections and other health problems.

Probiotics have also been shown to interact directly with the immune system, helping to reduce gut inflammation and reducing the body’s stress levels.

Not having enough probiotics in the gut can lead to imbalances of the microbiome, which has been linked to GI conditions like inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and even obesity, and type 2 diabetes.

Prebiotics:

Prebiotics aren’t living organisms like probiotics; they’re a substance that comes from fermentable fibers that we eat but cannot digest.

Prebiotics are essentially food for the probiotics in our gut.

Probiotics eat prebiotics and then ferment what’s left into what are called short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), for example, butyrate.

This process releases the neurotransmitter serotonin and anti-inflammatory agents which reduce stress signals to the brain.

Although more research is needed, it certainly does appear that regular consumption of both pre and probiotics can help regulate our hormones and therefore regulate our mood. One study out of Oxford University found that consumption of prebiotics can significantly impact the brain, lowering stress hormone (cortisol) levels and therefore lower the body’s stress response and anxious tendencies.

Here are a few probiotic-rich foods:

- fermented vegetables like sauerkraut and kimchi

- yogurt

- apple cider vinegar

- tempeh (fermented soybean)

You can also increase your intake of prebiotic-rich foods.

Prebiotics are non-digestible fibers that serve as food for your good gut bugs.

These include:

- garlic

- onions

- leeks

- asparagus

- barley

- bananas

- oats

- apples

- konjac root

- cacao

- flax seeds

- seaweed

- leafy greens

- jicama root

- dandelion

- Jerusalem artichoke

- chicory root

REFERENCES

:

(1) https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-anxiety-disorder-among-adults.shtml

(2) Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2008). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007. Cat. no. (4326.0). Canberra: ABS.

(3) https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/09/your-gut-directly-connected-your-brain-newly-discovered-neuron-circuit

(4) https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-human-microbiome-project-defines-normal-bacterial-makeup-body

(5) http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2014/11/14/363375355/how-bacteria-in-the-gut-help-fight-off-viruses

(6) http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v500/n7464/abs/nature12506.html

(7) http://www.nature.com/articles/npjbiofilms20163

(8) http://www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674%2814%2901236-7

(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24997034

(10) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4398233/

(11) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166432814004768

(12) http://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/09/gut-feeling.aspx